The above pics show Troy Towns in respectively Sweden, England and Scilly.

There are lots of labyrinths. There are Native American labyrinths, Roman labyrinths, South African labyrinths, and lots more. There is even a labyrinth locator.

Some Troy Towns bear other names such as Jerusalem, Ninevah or Babylon (Vavylon in Russia, where the B makes a V sound). They seem to have been especially numerous in the north, especially England, the Baltic Sea and the White Sea shores. The purpose of these constructions is not fully clear. There are plenty of things to read on the topic, and lots of interesting pictures. Including, for example, an extensive site about Swedish Troy Towns (in English): http://www.mymaze.de/trojaburg_en.htm

My first and most pressing question in this area is, do Troy Towns have anything to do with the ancient city of Troy? It is not clear that they do. Here is a quote from Troytowns by Haye Hamkens

Ernst Krause cites, in connexion with the name Trojaburg or Troytown, the Old German “drajan”, the Gothic “thraian”, the Celtic “troian” and the Middle English “throwen”. In addition there are the Anglo-Saxon “thrawan”, the Dutch and Low German “draien”, the Danish “drehe” and the Swedish “dreja”, and the English “throe”. All these words mean “turn” and were applied to the twists and turns of the layout. Perhaps also the “Wunderberg” used in the March of Brandenburg is a corruption of an earlier “Wenderberg”, in which case the word “wenden” (to turn around) would be the origin. The Low German word “traaje” also belongs here. It denotes a deep wagon track, a rut, and nowadays may be replaced by the word “spoor” (same in English). As a verb it means to follow in the track of another. In pronunciation the double a changes, as in the Nordic languages, to an almost pure O, so that “traajen” is pronounced like “trojen”. From here the inference would extend to the tracks, dug in the earth or formed from stones, which one must follow on entering the Troytown. When one views the spirals cut in the turf, which look like the tracks formed by a wagon, the relationship cannot be denied.

Full disclosure: the above work (in German) originally appeared in Germanien, which was a Nazi magazine, in the 1940s. The analysis shows that the word Troy in "Troy Towns" may be overdetermined with far more meanings than are needed to motivate the designation. A connection to the ancient city of Troy certainly need not be the only meaning, nor the primary one, nor any part of it, actually.

All of the derivations are Germanic, however, and it may be that the practice of naming walkable labyrinths after the city of Troy preceded these Germanic uses, perhaps in Latin or another language, such as Etruscan.

My next question is about the history of Troy Towns. Part of that involves the history of their main element, the labyrinth. Labyrinths differ from mazes. A labyrinth has only one path through it. A maze has more than one. The classical labyrinth has a near-circular shape.

There is an algorithm for producing a classical labyrinth, exemplified in the following gif figure.

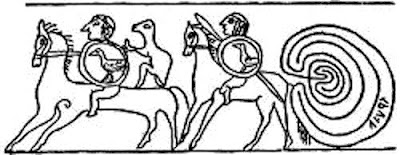

At the current time, the earliest example of the labyrinth symbol, for which an accurate and precise date can be determined, is on a Linear B inscribed clay tablet from the Mycenaean palace at Pylos in southern Greece.Accidentally preserved by the fire that destroyed the palace c.1200 BCE, the front of the tablet records deliveries of goats to the palace, the square labyrinth scratched on the reverse is clearly a doodle by the scribe. It is interesting that this earliest example should be found at the traditional home of King Nestor, who with Menelaos, raised the fleet of 'long black ships' to assist in the siege and subsequent downfall of Troy (dated by most scholars to c.1250 BCE), as recorded in Homer's Iliad.The depiction of a labyrinth on an Etruscan wine jar from Tragliatella, Italy, dating from the late 7th century BCE, shows armed soldiers on horseback running from a labyrinth with the word TRVIA (Troy) inscribed in the outermost circuit. This popular connection between the labyrinth and the defenses of Troy (and indeed other fabled cities) has continued throughout the history of the labyrinth, wherever it is found.Other finds point to an early spread of the labyrinth symbol around the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Two labyrinths scratched on a wall amidst the ruins at Gordion in central Turkey can be confidently dated to c.750 BCE and labyrinths recorded amongst rock art panels at Taouz in Morocco have been tentatively dated to c.500 BCE. Elsewhere, labyrinth graffitos and inscriptions have been found at Delos in Greece, in Egypt and Jordan, the majority dating from the first four centuries BCE and clearly the result of Greek and Roman colonization and trading influences in the region.

From the Tragliatella Wine Jug

The Tragliatella Wine Jug suggests that the word Troy was associated with labyrinths in ancient times. Suggests, not proves. The other side of the jug portrays another scene of what may in fact be a Troy Dance (which is the subject of a future post). The Etruscans were rumored to be descended from the Trojans. And Gordion, the Phrygian capitol, is not far from Troy.

Now that we know a little about the history of Labyrinths, how about the history of Troy Towns in particular? A Troy Town is a labyrinth laid out on the ground for people to walk in. "Troy Town" is just a name for these things. What does the world know about the origins of the practice of making walkable labyrinths, regardless of what they were called?

Many of the stone labyrinths around the Baltic coast of Sweden were built by fishermen during rough weather and were believed to entrap evil spirits, the "smågubbar" or "little people" who brought bad luck. The fishermen would walk to the centre of the labyrinth, enticing the spirits to follow them, and then run out and put to sea.

This passage suggests that the walkable labyrinth had mystical purposes. They are frequently found by the sea, and they might go back pretty far.

The period at which Troytowns were laid out has been the subject of lively debate. Dr Aspelin of Finland places Troytowns in the Bronze Age, while the Russian researcher Yelisseyev considers them even older. Dr Nordström of Stockholm was of the opinion that the designs were Christian ones, which were later transferred from churches into the open air. He based this interpretation on the fact that in many old Italian and French churches such mazes still exist as pavement mosaics. However, this must be erroneous, for Pliny reports in his Natural History (Book 26, 12, 19) on Troytowns in the open fields in Italy. Also the Greek and Egyptian labyrinths are much older than the Christian church. And it seems strange that such things should have developed when they have no foundation in the Christian religion. Actually the church took over Troytowns as it did many other things that for all its efforts it could not suppress. This is shown for example by the remarkable drawings in the vault of the parish church at Räntmaki in Finland. If the labyrinths set into church floors can at a pinch be explained as “the way to Jerusalem” etc., in the present case any such interpretation is impossible. For at Räntmaki the Troytown is drawn on the roof of a vault, among other drawings still apparently pagan in style. Thus only one conclusion is possible, that here a pre-Christian usage was taken over and given a new interpretation. Then during the Crusades the name “way to Jerusalem” emerged. To the same period belongs an East Prussian tradition of the Order of Teutonic Knights: in front of their castles the knights are said to have laid out mazes which they called “Jerusalem” and which they won in battle from their servants every day, amid laughter and joking. They did this in order to fulfil their vow that pledged them to unceasing struggle for the liberation of Jerusalem. Such is the tradition. It harks back to much older things and customs. And it can hardly be supposed that the knights occupied themselves with the Troytowns, nor constructed them. Much more probably, they built their castles and churches on the sites of such designs, as indeed nearly all old churches and monasteries were located on old sacred sites of pre-Christian times. ... It is a feature of all ancient designs, whether in Greece or Scandinavia, that while the rings have a common centrepoint, they are not exact circles, so that the centrepoint is displaced somewhat downwards. It can safely be assumed that the various windings of the Troytown symbolize the yearly course of the sun. The fact that there are 12 separate rings speaks in favour of this; for there are only a few Troytowns with any other division. The horizontal arms of the clearly visible cross are then perhaps to be regarded as the horizon, so that the various complicated and rather compressed turnings beneath it represent the sun’s path under the earth (during the night). Perhaps this is also the origin of the bad reputation of crossroads, which must similarly have a Pagan basis because otherwise it is quite incomprehensible that the holy symbol of Christianity should be the haunt of the Devil. The crossing point is often occupied by a stone or, in turf-cut designs, marked out as a square baulk. On it sat the imprisoned maiden, who had to be freed, as we know from many customs still in use today. Something of this is preserved in the well-known children’s song “Mariechen sass auf einem Stein” [Mariechen sat on a stone]. From many traditions and legends we know that bewitched people were changed to stone or banished into a rock. It is thus not too much to suppose that the sun as a maiden was exiled to a stone, guarded by a dragon, i.e. the winter, and that a knight, as spring, rescued her. The fact that these battles are often fought out in darkness or under the earth strengthens our hypothesis. For the Troytowns are regularly connected with the tradition of an imprisoned and rescued maiden, as has been briefly mentioned above for the Visby design, where the maiden actually appears as the builder of the maze. That she was kept prisoner under the Galgenberg (gallows hill), just as other Troytowns lie in the neighbourhood of Galgenbergs, again points to a pre-Christian origin and a subsequent satanization. ... In the oldest form of the Greek legend of Troy, Heracles kills the dragon before the gates of Troy and rescues Hesione.

https://www.cantab.net/users/michael.behrend/repubs/et/pages/hamkens_en.html

The above is another citation from Hamkens. His final sentence mentions an old story about Troy. Poseidon takes revenge on the King of Troy by putting a sea monster in his bay. Hercules slays the monster, and rescues Hesione, the king's daughter, who had been chosen by lot to be sacrificed to the monster.

Hamkens believes that the practice of laying out labyrinths to walk and play in is quite ancient. I have not been able to find the passages in Pliny mentioned above. An online search for "Troy" in his Natural History returned one hit that was not relevant. And Book 26 is about plants, not Italy.

I believe the practice of laying out labyrinths for ritual and festival and entertainment purposes probably is an ancient practice, long predating Christianity. On the age of the practice, I enjoyed a paper called Labyrinths in Pagan Sweden. The paper is based on place names rather than existing labyrinths, and argues that labyrinths were in use in Sweden from at least the early iron age.

Another connection between Troy and walkable labyrinths has to do with a rumor about the walls of Troy. In Homer, they are strong. In legend, they are complicated, like a labyrinth.

Caerdroea or Caer Droea is a Welsh word meaning "a labyrinth, a maze; maze cut by shepherds in the sward, serving as a puzzle." It also means "Troy, Walls-of-Troy". Variations include Caer Droia and Caerdroia, the latter being the spelling generally used today.

Because of the similarity between Welsh troeau (a plural form of tro 'turn') and the second element Troea ('Troy'), the name was later popularly interpreted as meaning 'fortress of turns' (caer = 'fort').[citation needed]

Many turf mazes in England were named Troy Town or The Walls of Troy (or variations on that theme) presumably because, in popular legend, the walls of the city of Troy were constructed in such a confusing and complex way that any enemy who entered them would be unable to find his way out.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caerdroia

This is our third connection. There is the Tagliatella Wine Jug, the story about Hercules and Hesione, and now the story about the complex walls. That is all we have to connect the city of Troy with the institution of the walkable labyrinth.

Recall that there are the labyrinths carved at Gordiam 500 years or more after the bronze age collapse. Those labyrinths are at least near Troy. What about at Troy itself?

The royal residences of the sixth and seventh city of Troy stood on concentric terraces, so that the innermost district was of a circular construction. This round structure continued in the trenches outside the fortress walls. In antiquity, concentric rings in the form of a labyrinth were in fact closely connected with Troy. Engravings on a wine jug from the Roman city of Tragliatella (around 620 BCE) depict a ceremonial “Troy dance” that was mainly performed when cities in early Italy were founded, and then, significantly, before the city walls were to be erected. Hundreds of stone labyrinths in England and Scandinavia bear names related to Troy, ranging from Troy Town to Trelleborg. Half a century ago, some experts assumed that a maze-like structure would eventually be discovered in the city plan of Troy. It is quite possible that this circular city plan also continued in the floodplain below the castle – and down there the trenches could have taken the form of navigable canals.

Concentric circles are not a labyrinth. But the connection between Troy and labyrinths could be based on something like it anyway. Atlantis was supposed to be composed of concentric circles. And the circles were supposed to be pierced or crossed by one, and only one avenue. Something like this.

Am I saying that the Atlantis story describes a labyrinth? No. The thesis that the Atlantis story describes a labyrinth is false. Read it for yourself.

But the proposition that the labyrinth design and the Atlantis design suggest one another is worth entertaining. It also offers another way of connecting Troy with labyrinths.

So now we have four connections: the Tragliatella Wine Jug, the tale of Hercules and Hesione, the rumor about walls so complex that attackers got lost in them, and something about concentric circles pierced by a single pathway. At least four things might connect the ancient city of Troy with the human passion for walkable labyrinths.

UPDATE:

I found some informative videos about this matter:

No comments:

Post a Comment